The “Only in America” Tour—Part 4

Dr Pepper and the Vanishing Period

Scoot over Pepsi, Dr Pepper is moving on up!

Dr Pepper went from being America’s fifth favorite soda in 2000 to now ranking No. 2, tied with Pepsi. Dr Pepper is growing fastest in popularity among Generation Z.

Sodas Ranked in Popularity in the U.S.A.:

- Coke

2. Dr Pepper and Pepsi

3. Sprite

4. Diet Coke

5. Mountain Dew

6. Coke Zero

7. Diet Pepsi

8. Fanta

9. Canada Dry Ginger Ale

As my friend Thea and I continued on our “Only in America” tour, we stopped in Waco, Texas. Thea threw away her empty Diet Coke bottle before we entered the Dr Pepper Museum.

Dr Pepper is America’s Oldest Major Soft Drink. It was invented in 1885 in Waco, Texas, and preceded Coca-Cola, which was invented in 1886 in Atlanta, Georgia, and Pepsi-Cola, which followed in 1893 in New Bern, North Carolina. These drinks were all invented by pharmacists.

Pharmacies initially began selling “fizzy” water to imitate mineral spring water and market its health benefits. They also used carbonated water and flavored syrups to make bitter medicines more palatable. Some companies started adding other elements to their sodas for their health effects. Coca-Cola famously added cocaine, and Pepsi added digestive aids. Apparently, the name “Pepsi” comes from a Greek word “dyspepsia” meaning “indigestion.” These sodas were sold as health drinks. (Please note: Coca-Cola removed the cocaine in 1903—just in case you were wondering.)

Back in 1893, at Waco’s Old Corner Drugstore, pharmacist Charles Alderton was busy trying different combinations of flavors in his free time. He kept a journal of his many experiments until he finally concocted a mixture he liked. His new drink had 23 flavors, which are the ones still used today in Dr Pepper.

The recipe for Dr Pepper is kept under lock and key, but here is a purported ingredient list that has circulated but has never been confirmed by the company: amaretto, almond, blackberry, black licorice, carrot, clove, cherry, caramel, Cola, ginger, juniper, lemon, molasses, nutmeg, orange, prune, plum, pepper, root beer, rum, raspberry, tomato, and vanilla. (Please note: the Dr Pepper Museum states that there is no prune juice in Dr Pepper. Apparently, that was only a rumor started in the 1930s.)

Also of note, the American Food and Drug Administration has ruled that Dr Pepper is not a cola, nor a root beer, nor a fruit-flavored soft drink. It is in a category of its own, called “pepper soda.”

The owner of the Old Corner Drugstore, Wade Morrison, is credited with naming Dr Pepper. There are many legends of the name’s origin, and none have been officially authenticated. But my favorite is that Morrison named it after Dr. Charles Pepper, a doctor from Rural Retreat, Virginia, who was the father of Ruth—Morrison’s love interest. Be it fact or a fiction, I must say I enjoy a good boy-pines-for-girl story.

Dr Pepper was introduced to a wide audience at the 1904 World’s Fair Exposition in St. Louis. Almost 20 million people attended. They discovered not only America’s oldest major soft drink, but for the first time, they were served hamburgers and frankfurters on buns. Moreover, ice cream was first served in large numbers in cones. It sounds to me like somebody ran out of containers and needed a way for people to eat food with their hands. Necessity is the mother of great American cuisine.

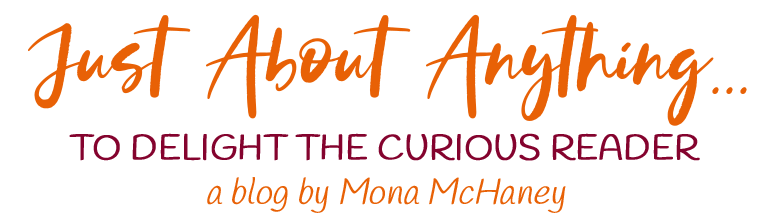

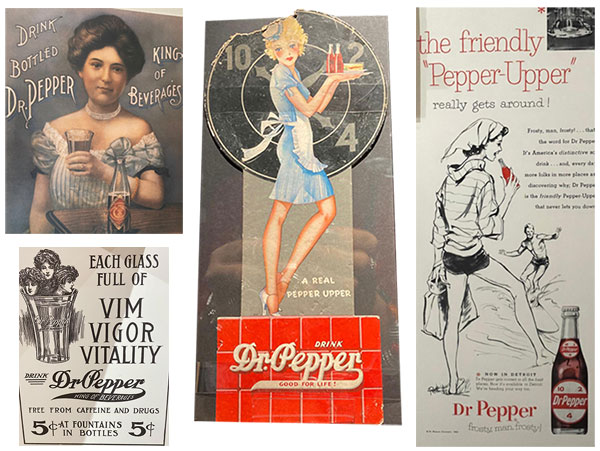

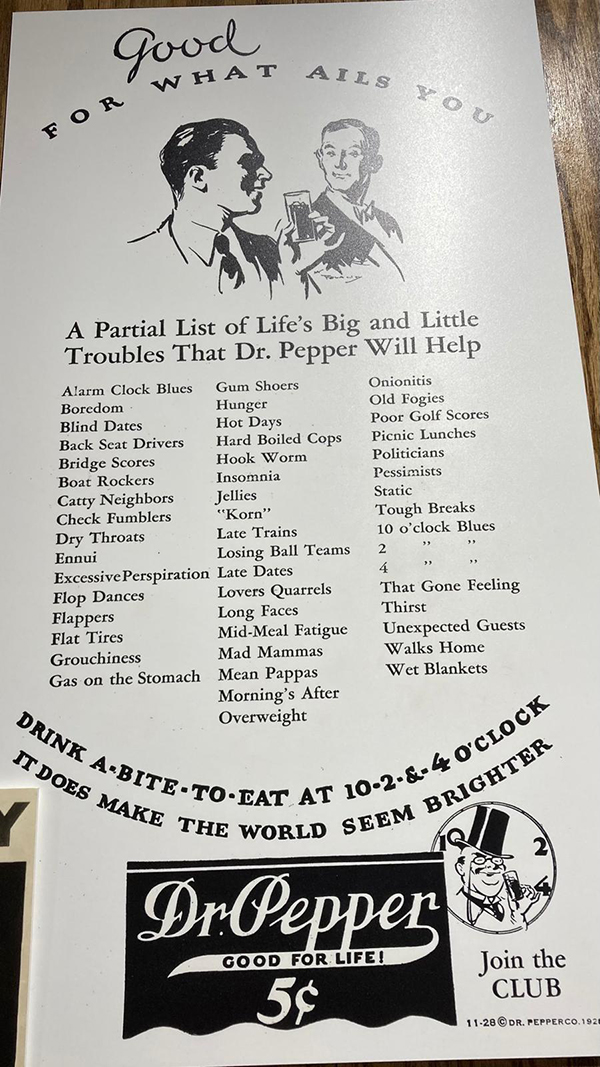

Over the years, Dr Pepper has promoted various slogans. It was the “King of Beverages” from 1910-1914. In the 1930s, when scientists identified the times when people have energy slumps, Dr Pepper’s jingle was “Drink a bite to eat at 10, 2, and 4.” In the 1950s, the drink was called “the friendly Pepper-Upper.” In 1977, the “Be a Pepper” campaign was launched.

Walking through the museum, I took photos of the different advertisements on posters. As I sorted through these pictures for this blog, I noticed something significant—and slightly painful—to a girl who teaches punctuation to foreigners: at some point Dr. Pepper dropped the period and became Dr Pepper. Apparently, this happened in the 1950s to make the name easier to read on the smaller bottles of the time. In a certain script, the “Dr.” ended up looking like “Di,” and that would never do.

One man helped make Dr Pepper an international brand: W.W. Clements, a.k.a. “Mister Dr Pepper.” Woodrow Wilson “Foots” Clements (1914-2002) began peddling sodas from a delivery truck in 1935 and eventually worked his way up to Chairman of the Board, President, and Chief Executive Officer. Hello, American Dream! Thank you, American Free Enterprise!

Foots listed his priorities as: God, country, family, and Dr Pepper. He adopted the Golden Rule as his guiding principle: “Do unto others as you would have others do unto you.” And another of his mottos captured his appreciation of collaboration:

“No ONE of us is as smart as ALL of us.”

I finished my tour of the museum at a replicated soda fountain. Here I ordered and drank a Dr Pepper float. Yum! It was another Texas businessman, J. Conrad Dunagan, who observed: “It can truly be said that carbonated soft drinks are modern America’s most popular contribution to the diet of the people of the world.”

The story of Dr Pepper combines many flavors of American culture: innovation, perseverance, free enterprise, hard work, the art of advertising, the allure of legends, the value of collaboration, and the pliability of punctuation.

P.S. An amendment to November’s blog “The Day America Lost Its Innocence”: One reader pointed out that although President Johnson issued Proclamation 3527 in 1963 to celebrate Thanksgiving Day on the fourth Thursday of November, Congress had previously issued a joint resolution in 1941 to approve this federal holiday. I stand corrected. I am thankful that “no ONE of us is as smart as ALL of us.”

Please encourage your friends and family to subscribe by emailing Mona.

Please encourage Mona at: encouragemona@gmail.com

I included a pdf download link below, which will print out nicely for all of my paper-loving readers.

Please feel free to share it with your family and friends.

Download a pdf version of this newsletter.